The password guessing bug in Tenex

In 1974, BBN computer scientist Alan Bell discovered a security flaw in the operating system Tenex. The password checking procedure would access certain memory pages during checking. By looking at which pages were accessed during checking of the password, user passwords could be guessed one character at a time.

The desire for virtual memory

Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN) was a company that initially specialized in acoustics. Because acoustic models required a lot of computation, BBN got interested in computing. In 1961 the company was the first to purchase a PDP-1 from the Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC).

The PDP-1 did not fully meet the requirements of BBN. The scientists at BBN wanted multiple users to be able to run memory-intensive LISP programs, and this required two features the PDP-1 did not have. First, they wanted time sharing functionality, so that multiple programs could be run in parallel. Second, they wanted virtual memory.

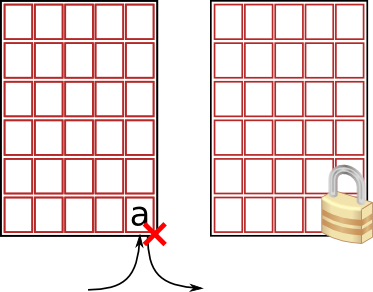

Virtual memory is a method of simulating more memory than a computer actually has. The memory space is divided in little memory blocks called “pages”. To make more actual memory available, some of these pages can be stored on disk when not in use. When a page is referenced that is not currently in memory, program execution is paused, the page is loaded from disk and put in memory, and execution continues.

The advantage of this “paging” system is that processes can use any memory address. They are no longer limited by the amount of physical memory, or the parts of memory that other processes use.

BBN was one of the first to see the advantage of paging, but the advantages weren’t obvious to everyone. According to Dan Murphy, who worked at BBN from 1965 until 1972: “Then too, paging and “virtual memory” were still rather new concepts at that time. Significant commercial systems had yet to adopt these techniques, and the idea of pretending to have more memory that you really had was viewed skeptically in many quarters within DEC.”

At BBN they implemented paging for the PDP-1 in software. Although it worked well, it was pretty slow. “However, the actual number of references was sufficiently high that a great deal of time was spent in the software address translation sequence, and we realized that, ultimately, this translation must be done in hardware if a truly effective paged virtual memory system were to be built.”

At this time the world of computers was in its infancy and it was not yet very clear which features a computer should have. BBN thought it should at least have time sharing and virtual memory, and it tried to convince computer manufacturer DEC to provide such a system. BBN asked DEC to design a PDP-6 with paging, but eventually DEC stopped producing PDP-6 models without there ever having been paging support.

Creating a paging computer

BBN could not convince a computer manufacturer to create a paging computer that conformed to their wishes. In 1969 they decided to build a system themselves that implemented paging in hardware.

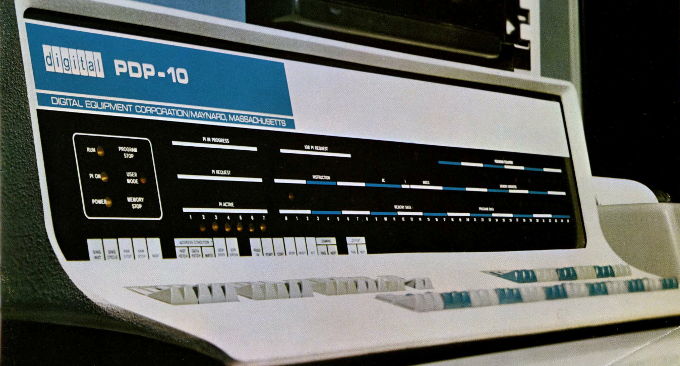

BBN purchased a PDP-10 to modify it to fit their needs. The standard PDP-10 had insufficient hardware support for paging. However, it was built in a modular way that made it possible to change some components. BBN took advantage of this by designing their own hardware module to do the paging, and placed it between the processor and the memory. This photo by Dan Murphy shows the BBN pager, as the hardware module was called:

To support this hardware module in software, and to implement some other wishes they had, BBN decided to implement their own operating system: Tenex. In approximately six months a small team of computer scientists created a new operating system that finally conformed to the wishes of BBN.

Virtual memory under Tenex

With Tenex, BBN finally had a system with full virtual memory support. Each program under Tenex could use the full address space for addressing memory. Furthermore, programs had a lot of control over the paging. Alan Bell writes: “The virtual memory system allowed the user a lot of control over what pages were placed in the address space. While usually a paging file was in the address space, it was also possible to map data files, etc. Therefore, the user was given control over what was mapped where and the type of access allowed.”

One of the paging settings was the “trap to user” bit. This would cause an interrupt to the program whenever a specific page was accessed. This was generally not very useful, but proved an easy way to exploit the password guessing bug described later.

Checking the password

Like many modern systems, Tenex supported multiple users that could authenticate themselves with passwords. The operating system provided a system call to check user passwords. “This password checking JSYS was given a user name string and a password string. It would return success or failure. To prevent quickly trying many passwords, it delayed returning to the user code for 3 seconds on failure.”

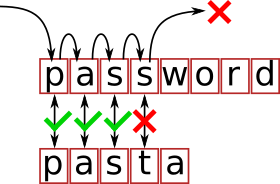

The two passwords, the correct one in the system and the one supplied by the user, were compared using a standard string comparison algorithm: one character at a time. “The algorithm would step down each character in the strings, making the comparison. It would indicate failure as soon it saw a disagreement. If it got too the end of both strings, it would indicate success.”

Discovery of the bug

Because of how the password checking was done it accessed certain memory locations depending on what part of the password was correct. Which memory locations it accessed could be determined by using the paging system. This made it possible to guess user passwords one character at a time, which was a serious security flaw.

This bug was discovered in 1974 by a young computer scientist, Alan Bell. Alan joined BBN just a year before and was interested in Tenex, which was the most complicated piece of software that he encountered so far. He read the source code of the operating system in his own time to figure out how it worked, and this is how he discovered the flaw. “At one point, I looked at the password checking routine and saw the flaw. I implemented code to exploit this flaw, proved that it successfully worked, and ran it on a few system accounts to verify that.”

Exploiting the bug

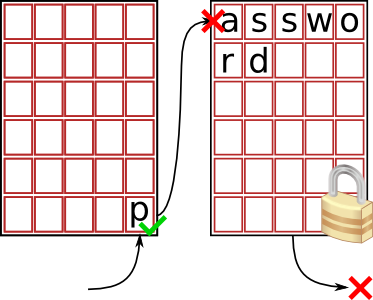

To exploit the vulnerability, Alan wrote a program that would place the first character it didn’t know at the end of the page, with the rest of the string on the next page. The next page would have the “trap to user” bit set to detect any access to the page. If the character was wrong, the OS would never access the characters on the next page and would return false after a three second delay. If the character was correct, the OS would check the next character, which would access the next page and cause a trap to the user.

The trick was to put the password to be checked on the edge of two consecutive pages. The second page would have the “trap to user” bit set, so that any access to the page would trigger an interrupt. If the character on the first page was incorrect, the system would delay for three seconds and report that the password is incorrect:

If the first character is correct, however, the checking procedure tries to access the second page. Because we set the “trap to user” bit on this page, an interrupt is caused when trying to check the second character.

These different behaviors are distinguishable from the user program. This means we can carefully align the password and try different letters until we receive an interrupt. At that point we know that the character is correct, and move on to the next character. Alan’s program did just that, and guessed the program one character at a time. “So the password would slowly be typed on the terminal with each character coming out after an average of 30-40 seconds. This would continue until the password was complete.”

Alternative exploits

Alan used the “trap to user” bit to detect whether a page was accessed, but this was only one of the ways it was possible to detect page access. It would also be possible to turn off read access on a page, so that an error occurred as soon as the password checking procedure would try to read from the page. Another possibility was to not map the page at all, and checking whether it was created after checking the password.

It would also be possible to exploit this bug using a timing attack. “The amount of physical memory was in the range of 64K words and the virtual address space was much larger so it would have been easy to force pages out of physical memory by accessing other pages. One could then time the access.”

Fix

After finding the bug and proving that it was exploitable, Alan told Ray Tomlinson (famous for inventing email) over lunch. Later that day, Bob Clements created a patch to fix the issue. The solution he came up with was to reference the first and last character before doing anything, so that page access no longer depended on the password: “I put the patch in, and made it as trivial as possible to get it out in the field. Test the eighth word before doing anything. That would give you a bad memory reference immediately if you were playing against the page boundary. Otherwise, drop into the 39 character loops.”

Release procedure

In 1974 there was no responsible disclosure yet and not many companies had experience with fixing security bugs. “Computer security research was basically non-existent in 1974. So I simply saw this as a bug in the OS as opposed to something more important.”, writes Alan. Even so, BBN took care that all sites running Tenex would receive the patch at approximately the same time. “They sent an email to all the sites running Tenex saying that an important security patch was forthcoming at a particular time. They didn’t want people exploiting it by getting the actual patch before others.” At that time there would be between a dozen and two dozen sites with Tenex machines.

Encrypted passwords

With the fix Bob Clements put in, the behavior of the password check could no longer be determined from the page access. However, developers at BBN soon became aware that storing passwords in plaintext was not very secure to begin with. Bob writes, “A day or so later, someone realized that relying on keeping plaintext copies of passwords in the system files was not a smart thing to do. So we created encrypted passwords.” Bob Thomas wrote the encryption code, and Bob Clements changed the password checking mechanism.

“We encrypted the passwords so you had to compare the encrypted form of the password with the pre-stored version of the encrypted password. At no point was the un-encrypted password in memory except briefly when you first created the password and then briefly when you threw the plaintext up against the encrypted version. This was a lot like modern Unix.”

Conclusion

BBN was a pioneer at start of the computing era, and successfully implemented and promoted virtual memory, a feature that is now in almost every computer and operating system. Alan Bell used this feature to determine memory access and exploit a security flaw by guessing passwords. This is a typical example of a side-channel attack, where the behavior of a program is determined without communicating directly with the program. Such side-channel attacks are still relevant today, for example the cache timing attack on AES. BBN handled the vulnerability admirably by distributing a patch within days of finding the bug.

Read more

- TENEX and TOPS-20, Dan Murphy

- “Tenex hackery” in alt.folklore.computers

- TENEX, a paged time sharing system for the PDP-10, Daniel Bobrow, Jerry Burchfiel, Dan Murphy, Ray Tomlinson