I made a client-side spamfilter for Tutanota email

I created a spamfilter that runs in the browser for my personal email.

Introduction

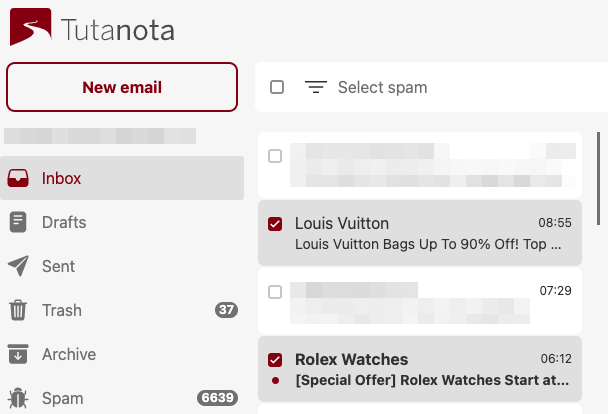

When Google Workspaces started charging money, I switched to another email provider: Tutanota. They are great in many ways, but the spam filter is not very good. I got dozens of spam messages each day. Often I get the same spam message multiple times. These show up in my inbox, even after I reported an email as spam. I was getting tired of this, and decided to do something about it. I made my own client-side spam filter.

Design

Tutanota doesn’t have IMAP or something that would make it possible to retrieve and filter messages in a standard way. I mainly use the Tutanota web app from the browser, and decided to implement the spam filter there, using JavaScript. A browser extension can inject my spam filtering script in the Tutanota web app.

The filtering logic doesn’t have to be very complex. I can often determine whether a message is spam just by skimming the subject and the sender, and I figure an automated filter could do the same.

Reverse engineering the API

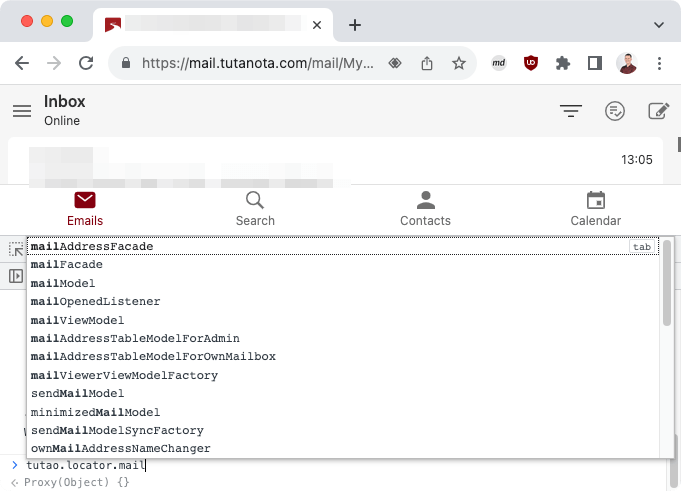

My JavaScript spam filter needs access to emails, so I wanted to hook in to the Tutanota web app. I tried some things in the browser console, and looked at the source code of the Tutanota web app, and after some time I figured out how to retrieve emails.

There’s a global tutao variable that offers an entry into the Tutanota internals.

Most web applications have such a global variable, but this is not necessarily the case. It is entirely possible to implement an application without using global variables.

The code to retrieve the inbox from the current mailbox is quite straightforward:

tutao.locator.mailModel.getMailboxDetails().then(

details => inbox = details[0].folders.getSystemFolderByType("1")

);

However, it is less straightforward to retrieve the mails in this folder. The inbox does have a mails property, but it is an identifier, not a list of emails. Instead, we have to pass identifier to the EntityClient to load a list of mails. Emails, contacts, and calendar items are all forms of entities, and these are all loaded in the same way.

The EntityClient has functionality to load emails (or other entities) starting from a certain email, again indicated with an identifier. This is a common pattern used for pagination. It makes it easy to only retrieve and learn new emails. We remember the identifier from the last email we saw, and request only newer emails.

Many functions within Tutanota and the classifier are asynchronous. Asynchronous function return a Promise, and I handled that explicitly by calling then() on the promise and creating new promises to return. I feel like using await and async keywords better could improve things, and I am missing some understanding here how this works exactly.

The code for the Tutanota web app is open source. However, it is written in TypeScript and then compiled and packaged into a JavaScript bundle. This step removes some useful metadata. That’s why I call getSystemFolderByType("1") and not getSystemFolderByType(MailFolderType.INBOX): the values from MailFolderType are inlined when compiling to JavaScript, and the type itself is no longer available.

Functions within TypeScript that are defined as public survive the translation to JavaScript and keep the same name. Some private functions also keep their name, but most are mangled. I currently use some of the private functions that kept their name, but this may be fragile. A recompilation of the app may inline the private function or name it differently.

Running script on the page

I created a browser extension with a content script that runs on the Tutanota mail app. A content script has access to the DOM, but still runs within its own context. Since I want to hook into the Tutanota JavaScript, I want to access the global variables in the page. This is not possible from the content page, but it is possible to add a script to the page itself. So my content script does nothing else than adding another script to the page. That scripts can access the global variables that contain Tutanota functionality:

const script = document.createElement('script');

script.setAttribute('src', chrome.runtime.getURL('page.js'));

document.body.appendChild(script);

The plugin adds a button to the UI, which selects all spam. This button needs to be added just after the Tutanota app is finished loading. I tried to hook into the Tutanota app to get a notification when this is the case, but in the end I decided to keep polling for a <div> with the correct name. Less elegant, but it works.

Naive Bayesian classifier

Thomas Bayes invented some statistics rules, which today help us to filter spam. Specifically, when a word occurs more often in spam than in normal messages, it gives us some information on whether a message is spam if it contains that word. A Bayesian classifier can automatically learn which words fit which categories, and then assign some probability that a message belongs to a certain category. It is naive in the sense that it considers the words and probabilities to be independent: it calculates the probability for “vicodin” and “pills” separately, even though these may in practice only occur together.

NPM has at least 50 implementations of Bayesian classifiers in JavaScript. I chose one, and just copy-pasted the code into my script, instead of messing with a build environment. It has a simple API:

classifier.learn('Buy Vicodin Pills Today', 'spam');

classifier.learn('Schedule week 38', 'ham');

classifier.categorize('Cheap Vicodin Pills'); // => 'spam'

The categorize function calculates the probability of each category, and returns the most likely category. This may give unexpected results if it is not very sure about the category. If it is 1% certain it’s ham and 2% certain it’s spam, it will be marked as spam, even though it basically doesn’t know. This gave unexpected results while developing, but it doesn’t really give problems in practice.

In the example above, we pass a sentence to the API, but the classifier learns on words. The input is split into words by a tokenizer. I began with passing the subject to the default tokenizer, but later on I changed this in a couple of ways. First, a special token is added when the subject is empty. An empty subject of course does not match any words and would be hard to classify, but the fact that it’s empty is a good sign that it’s spam. To inform the classifier of this, I add a __emptySubject token when the subject is empty. Second, I don’t split the recipient address into separate words. That something is sent to sjoerd-github@linuxonly.nl is useful for the classifier, and shouldn’t be confused with a subject that contains “Sjoerd” and “GitHub”. Third, I made the tokenizer case-insensitive.

After changing the tokenizer, the classifier does not work correctly anymore and needs to be retrained. Before making the tokenizer case insensitive, it learned about “GitHub” and “VICODIN”, and now it only sees mails about “github” and “vicodin”. I forgot this step a couple of times, and then it looks like the change to the tokenizer made the classifier a lot worse.

I store the classifier in the browser’s localStorage, so that it keeps persisted and I can use and update it every time I open the mail app.

Conclusion

The spam filter works well. The Bayesian filtering was easier than I expected. Integrating with the Tutanota app was the biggest challenge. Because the Tutanota app does not have a well-defined API, I feel like my spam filter could stop working when they push a new update of their app. But until that time, I have an easy way to handle my spam problem.