Cross site request forgery (CSRF)

This article describes how cross site request forgery works, how sites defend against it and how to bypass these defenses.

What is CSRF?

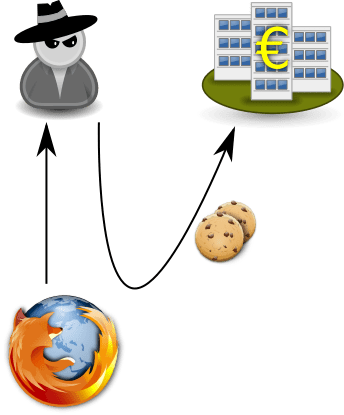

When you are logged in to a certain site, you typically have a session. The identifier of that session is stored in a cookie in your browser, and is sent with every request to that site. Even if some other site triggers a request, the cookie is sent along with the request and the request is handled as if the logged in user performed it.

Cross site request forgery (CSRF) is performing a “forged” request from the attacker’s site to another site where the victim is logged in. If that site is vulnerable, any action that the user could normally perform on the site can now be performed by the attacker.

Example

Suppose you are logged in to a web application that has a button “Delete all data”. When pressing that button, a request is performed to “https://my.webapp/DeleteAllData?doit=true”.

Now, the attacker creates a web site with the following HTML code:

<img src="https://my.webapp/DeleteAllData?doit=true">

When you visit the attacker’s site, the request is performed to “https://my.webapp/DeleteAllData?doit=true” and all data is deleted, even though you haven’t clicked the button.

What requests can be performed?

CSRF works by triggering a request from one site to another. However, not all requests can be sent just like that. The request has to conform to some arbitrary rules. Requests with the following properties are allowed:

- The request method is one of

- GET

- HEAD

- POST

- The request does not use any custom headers.

- The content type is one of

- application/x-www-form-urlencoded

- multipart/form-data

- text/plain

Any other request triggers a preflight request. This is an extra check on whether your request is allowed, and your request will most likely be blocked.

Notably, you can’t perform a request with content type application/json, which is pretty popular in web apps. However, you can still post JSON using a content type of text/plain, and it depends on the application whether this works or not.

Which actions should be protected against CSRF?

Requests that have some side-effect should be protected against CSRF. For example,

- requests that modify data in the database, such as saving or deleting an entry.

- requests that modify data in the current session, such as changing the user’s language or logging out of the application.

- requests that perform some action, such as sending an email or sending a text message.

With CSRF the vulnerability is that any other website can trigger this side effect. If there is no side effect the attacker can still trigger the request, but that doesn’t do anything.

GET and POST

For CSRF we are interested in requests with some side effect. Most of the time these are POST requests, but not always. Some sites do have CSRF protection on all POST requests, but not on GET requests. In that case it is interesting to search for a GET request that performs some action.

Some sites don’t care if you sent the data using GET or POST. A POST request can then be converted to a GET request, by including the parameters in the URL instead of the POST body. If the site then only checks for CSRF on POST requests, this effectively bypasses the CSRF protection.

Which actions are interesting for CSRF?

An interesting action to perform through CSRF is changing the password or email address, as this results in account takeover. For passwords this is often impossible since you have to fill in the old password, but for email addresses this is sometimes forgotten.

Another interesting action is to create a new user for the application, typically by an administrator. If this action can be forged by an attacker, he can gain access to the whole application.

One request that can often be forged is to log out the user. On most sites, simply visiting /logout or something like that will log out the user. This is technically CSRF, although with a rather mundane impact.

Common CSRF protections

Random token

CSRF protection is typically done by sending a random token along with any request. The attacker won’t have this token and thus can’t forge a valid request.

If implemented correctly, this is an adequate protection against CSRF. If a site uses this method, you can check for the following weaknesses:

- Is the token actually checked everywhere? That a token is present in the request is no guarantee that requests without tokens are blocked.

- Is the token long and random enough? If the token is short and predictable, it may be possible to brute force it during a CSRF attack.

- Is the token generated using a secure cryptographic random number generator? Using

rand()often does not provide enough security. - Is the token bound to a user’s session? If a token can be used with another user’s session, the attacker can use his own token in the CSRF attack.

Referer check

Sometimes the site verifies the Referer or Origin headers to verify that the request came from the site itself. This can be secure, but is hard to get correct.

Sometimes the site checks whether “https://www.example.com/” is contained in the Referer, in which case it can be attacked by using “https://www.attacker.com/?https://www.example.com/” as the attacking page. Also a subdomain can be used, like “https://www.example.com.attacker.com/”, if only the start of the referer is compared.

Some browsers don’t submit a Referer header in their requests. Some anti-virus software remove the header to prevent leaking URLs to other sites. If the web application should work correctly with those browsers, it must handle the case of a missing Referer header. However, this opens the case for CSRF attacks. By using a referrer policy, the Referer header can be removed from a request. A forged request can be made without Referer header, possibly bypassing the CSRF protection.

Same-site cookies

Finally, same-site cookies provide adequate protection against CSRF, but only for browsers that support them. Same-site cookies are only sent for requests from the same site. In cross-origin requests, such as with CSRF, the cookies are not sent. This means the forged request is not authenticated and can’t perform some action as the logged-in user.

The same-site cookie flag has two possible values:

- Lax, only POST requests are stripped of authentication.

- Strict, all requests are stripped of authentication.

This means that if there is a GET request that is vulnerable to CSRF, it is still vulnerable even when Lax same-site cookies are used.

Conclusion

Cross site request forgery remains a threat that is hard to defend against. Web app frameworks often offer a protection against CSRF, but often every action that needs protection has to be marked explicitly. This makes that modern web applications still contain some CSRF vulnerabilities.