MySQL's random number generator

MySQL and MariaDB have a RAND function that is supposed to return random numbers. However, the numbers it returns are not particularly random.

How it works

MySQL and MariaDB both have a RAND function that returns a “random” number. From the MariaDB docs:

Returns a random DOUBLE precision floating point value v in the range 0 <= v < 1.0.

The pseudorandom number generator (PRNG) keeps two state variables, and modifies them each time it is called as follows:

seed1 = (seed1 * 3 + seed2) % 0x3FFFFFFF

seed2 = (seed1 + seed2 + 33) % 0x3FFFFFFF

return seed1 / 0x3FFFFFFF

You can find the source for MySQL and MariaDB.

Seed

The initial values of seed1 and seed2 are derived from the current time. A global PRNG instance is first seeded with the time in seconds:

my_rnd_init(&sql_rand,(ulong) server_start_time,(ulong) server_start_time/2);

Then a thread-specific PRNG is seeded from the global PRNG, plus something:

tmp= (ulong) (my_rnd(&sql_rand) * 0xffffffff);

my_rnd_init(&rand, tmp + (ulong)((size_t) &rand), tmp + (ulong) ::global_query_id);

::global_query_id is a query counter, which is always 1 when the server starts.

(ulong)((size_t) &rand is the current address of the thread-specific PRNG structure in memory. It is different for each thread.

The PRNG is seeded when a new thread is created, but not when a new connection is established.

Problems

30 bits

The operations are performed modulo 0x3FFFFFFF, or 230 - 1. So the random numbers contain at most 30 bits of entropy, or a little over one billion possible outcomes. If you try to create random numbers bigger than that, some numbers will never be chosen. For example, the following query always returns an even number:

SELECT RAND() * 0x7FFFFFFE;

Modulo 33

There are three operations performed in the random number generator:

- addition of 33,

- multiplication by 3,

- modulo 0x3FFFFFFF.

0x3FFFFFFF is cleanly divisible by 33. If the random number generator is seeded by values that are divisible by 33, they remain that way. None of the above operations are going to change a number that is divisible by 33 to one that is not.

This also holds if the seeds are divisible by 11. None of the operations above are going to change the seed to something not divisible by 11.

If the seeds are not divisible by 33 or 11, the random number generator still gets stuck in a group where it only generates certain numbers modulo 33.

This affects only the least significant bits, so when doing RAND() * 10 this won’t be noticeable. However, it does significantly reduce the number of usable bits in the PRNG. With a seed that is divisible by 33, the following query returns only even numbers:

SELECT RAND() * 65075262;

Seeds

The global PRNG is seeded with the current time, and the current time divided by two. These values are not particularly random, and they are also related to each other. Above we said that the PRNG behaves badly if both seeds are divisible by 11. If both seeds were independent, this would happen once every 11×11 or 121 times. However, because seed2 is half of seed1, this now happened every 22 times.

The thread-specific PRNG is also not seeded very well. First of all, a variable common to both seeds is created:

tmp= (ulong) (my_rnd(&sql_rand) * 0xffffffff);

However, my_rnd here returns a 30-bit random number between 0 and 1. Multiplying this with 0xffffffff tries to create a 32-bit random number from a 30 bit random number. As a result, the lower bits are not particularly random.

Next, it initializes the thread-specific PRNG:

my_rnd_init(&rand, tmp + (ulong)((size_t) &rand), tmp + (ulong) ::global_query_id);

It adds a memory address to the first seed. Since structures are aligned in memory, this is always a multiple of 8, but that is not really a problem after the PRNG reduces it to modulo 0x3FFFFFFF. If the system has address space layout randomization (ASLR), the kernel puts the process in a random place in the memory address space. The address &rand will also be pretty random, causing a good seed for the PRNG.

ASLR is supposed to keep the memory addresses secret, to make it harder to exploit buffer overflows. Using an address as the seed for the PRNG exposes a bit of information of the address space to the user. This could compromise ASLR: an attacker can read the seeds of the PRNG and determine where the process is in memory. The PRNG exposes only a little bit of address information, but this pattern of using memory addresses does come with a security risk.

Even though the process is in a random place in memory, the data for the threads are all in the same process. So the seeds of the different thread-specific PRNGs differ from each other by a specific non-random amount.

Low seeds

If both seeds are low, the values don’t wrap around. If the values are well below the modulo (0x3FFFFFFF), the operations of ×3 and +33 are just that, and the output just becomes slowly bigger with each step.

MariaDB> set session rand_seed1 = 123, rand_seed2 = 456;

MariaDB> select * from numbers order by rand();

+------+

| num |

+------+

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

+------+

10 rows in set (0.001 sec)

There are more seeds that exhibit such stable behavior, such as 0x3FFFFFFF / 3.

Repetitions

MySQL’s PRNG is also prone to repeating itself with relatively high probability after a certain number of iterations.

If we create two lists of n random numbers, what are the chances that the top entry of both list is the same? In other words, does the PRNG repeat itself after n calls? For a 30 bit PRNG, we would expect this chance to be 2-30, regardless of n. For MySQL’s PRNG, this chance is higher then expected for some n:

- n = 960, probability of 1/449829, 2-19

- n = 22800, probability of 1/92349, 2-16

- n = 91200, probability of 1/2979, 2-12

Low period

The PRNG returns to the same state after at most 83265600 iterations, after which is repeats the same sequence. This is a little bit over 226. For a PRNG that keeps 60 bits of state, we would expect this to be closer to 260.

Distribution

A simple way to pick a random row from a relatively small table is as follows:

SELECT * FROM table ORDER BY RAND() LIMIT 1

This returns the row for which RAND() returns the lowest value. For some table sizes, this performs quite bad. If the table is 2400 rows, some items are 40 times as likely to be picked as some other items.

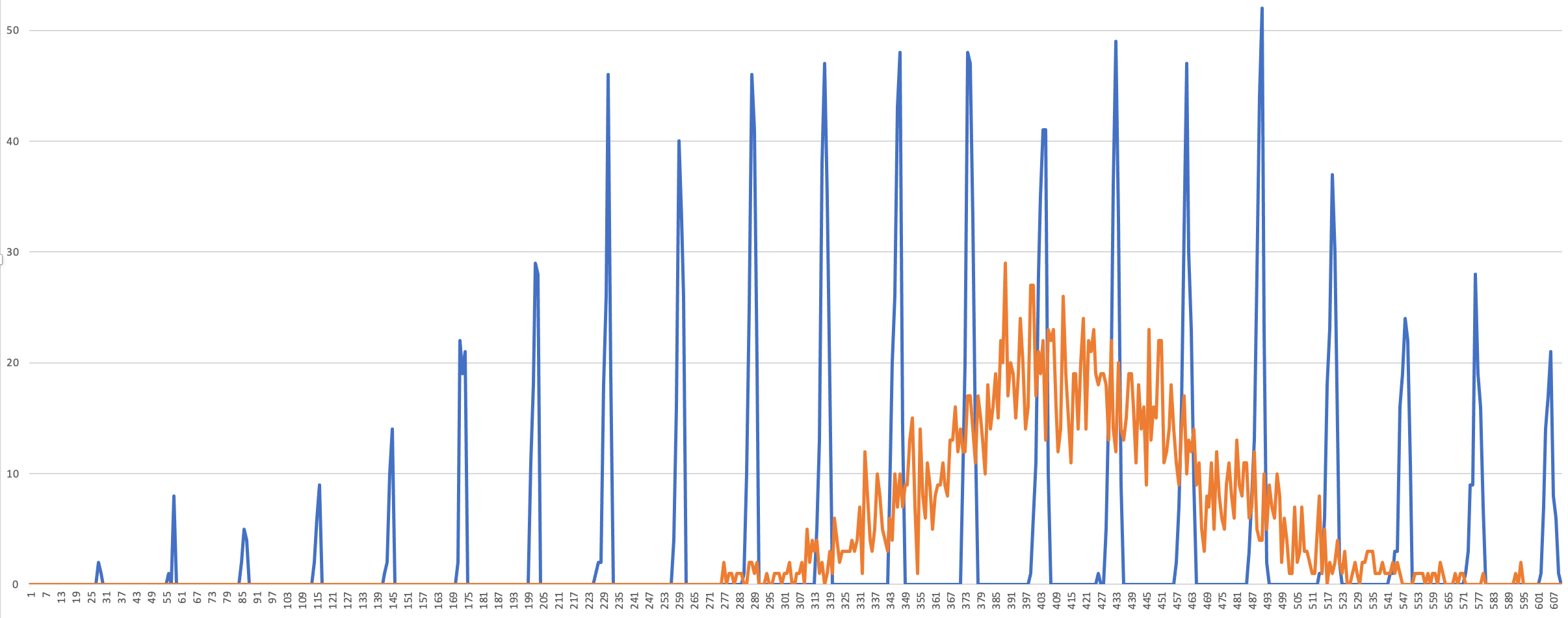

I simulated the above query a million times and plotted the results in a graph. The orange line shows the distribution for an actual random sample. The blue line shows how many times items are selected with simulated ORDER BY RAND() queries in a table of 2400 rows.

The x-axis shows the number of times a certain row is picked, and the y-axis shows how many rows are picked this many times. For example, at the first blue peak on the left, we see that there are 2 rows that are picked 28 times. For the orange, truly random series, we see a normal distribution around 420, as expected. For the blue, MySQL RAND series, we see really non-random behavior. Some rows were picked 460 times, some rows were picked 490 times, but not a single row was picked 475 times.

Also, the distribution is much wider than expected. Some rows were picked only 28 times, which is very unlikely with a random distribution.

The position of these spikes change when the PRNG is reseeded. So regularly reseeding the PRNG may give better distribution of chosen rows.

Fixed point

Seeds exist for which the PRNG gets stuck in a loop, and always generates the same “random” number. For example:

- seed1 = 1073741790 = -33 (mod 0x3FFFFFFF)

- seed2 = 66

In a round of PRNG, it does:

- seed1 = seed1 × 3 + seed2, so seed1 = -33 × 3 + 66 = -33

- seed2 = seed1 + seed2 + 33, so seed2 = -33 + 66 + 33 = 66

Both seeds remain the same, so the PRNG always outputs the same number.

Points fall in a plane

Below is a three-dimensional plot of 30,000 values generated with MySQL. Each point represents three consecutive pseudorandom values. All points fall in one of eight planes, showing that the PRNG is not very good at generating random numbers.

Conclusion

MySQL’s random number generator:

- is seeded with low entropy, related values.

- returns at most 30 bits of randomness by design.

- gets stuck in groups modulo 99.

- returns predictable sequences for unlucky seeds.

- repeats itself with higher probability after specific number of calls.

- has a relatively short period, after which it returns the same sequence.

- has a skewed distribution when selecting random items from tables.

- has fixed points in which it returns the same number over and over.

- creates points that fall on one of several tree-dimensional planes.

In short, it isn’t very random.