Hacking the Motorola MBP88Connect WiFi camera

The Motorola Wi-Fi Video Baby Monitor Camera (MBP88CONNECT) is a webcam that can be controlled and viewed using the Hubble mobile app and Hubble web app. I found several vulnerabilities in the camera’s web interface, which have been resolved by the distributor through firmware updates. This article describes the vulnerabilities and how I found them.

Setup

The camera can be put in pairing mode using a button on the camera itself. In pairing mode, the mobile app can be used to connect the camera to the Hubble account. In pairing mode the camera works as a open WiFi access point. The phone connects via WiFi and initializes the camera. After that, the camera can connect to the normal WiFi.

Camera on the local network

The Hubble server acts as a service to connect phone and camera, but the video stream is sent directly over the WiFi, not over the internet. This means that the camera can only be viewed when the phone and the camera are connected to the same WiFi network. This gives a little bit of a security advantage, since the camera is not connected directly to the internet.

For this security test, I shared my network connection over the WiFi, making my laptop a WiFi access point. I configured the camera to connect to my laptop access point, so that all traffic goes through my laptop and can be intercepted.

Discovery

After setting up the camera, I run a port scan to discover any services on it:

$ sudo nmap 192.168.2.16 -p 0-65535

Starting Nmap 7.70 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2018-08-06 10:14 CEST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.2.16

Host is up (0.040s latency).

Not shown: 65530 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

80/tcp open http

6667/tcp open irc

8080/tcp open http-proxy

51108/tcp open unknown

60000/tcp open unknown

60001/tcp open unknown

MAC Address: 00:0A:E2:4F:B0:20 (Binatone Electronics International)

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 73.29 seconds

There seem to be two HTTP interfaces, on port 80 and port 8080.

Scanning HTTP services

There are two tools that I run on any HTTP server:

- dirsearch

- nikto

Dirsearch tries to find files on the server. It simply requests a lot of files and lets you know which ones exist. This does not indicate any vulnerability, but may give an entry point to test some undiscovered functionality. Nikto is an automatic scanner that searches for vulnerabilities. I don’t think it’s very good and you can’t trust anything it says, but it’s automated so it can give some clues without any effort on my part.

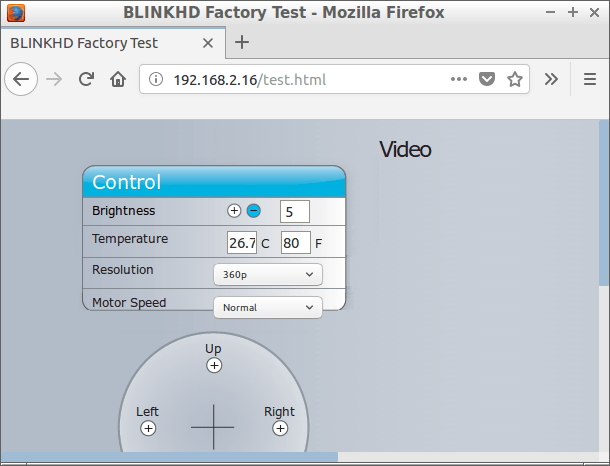

Dirsearch detects test page

Running dirsearch indicates that there is a test.html page on the camera server. This gives a page that allows to control the camera. Supposedly you could also view the video stream here, but that doesn’t work. But we can move the camera, play sounds, and view the temperature. We can do all this without having authenticated. The mobile phone was paired with the camera and should be able to control it, but this page makes it possible for anyone that can connect to the camera to control it.

Test functionality in production environment

This page is titled BLINKHD Factory Test. From this I assume that it is used to test the camera after manufacturing. However, it shouldn’t be left on the camera when it’s shipped to users. Leaving test code in a production system exposes unnecessary functionality that increases the attack surface.

Missing authentication

This camera has little authentication. Pairing the camera to the phone during setup doesn’t actually create a trusted connection. Anyone that can perform a request to the camera can control its motion, play sounds, or view video.

Cross-site request forgery

Any user on the same network can perform such a request, but also anyone on the internet with a website. If you have a camera at home and browse to a website, that website can cause a request to the camera. This is known as cross-site request forgery: the site on the internet “forges” a request to the camera. For example, putting the following code on a website makes the camera move to the left:

<img src="http://192.168.2.16/?action=command&command=move_left">

Nikto detects path traversal

Running Nikto gives the following interesting result:

+ /..\..\..\..\..\..\temp\temp.class: Cisco ACS 2.6.x and 3.0.1 (build 40) allows authenticated remote users to retrieve any file from the system. Upgrade to the latest version.

+ /../../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd: It is possible to read files on the server by adding ../ in front of file name.

This doesn’t seem like a Cisco system, but it looks like the server may be vulnerable to path traversal in the web server. For example, the following command line retrieves the /etc/passwd file:

$ curl --path-as-is http://192.168.2.16/../../../etc/passwd

root:x:0:0:root:/:/bin/sh

nobody:x:99:99:Nobody:/:/sbin/nologin

ftp:x:501:0:ftp:/var:/bin/sh

usb:x:504:100::/usb:

Path traversal

Path traversal originates from concatenating user input to obtain a directory. In our case, the webroot is /mnt/skyeye/mlswwwn. This directory contains the files that are available on the webserver, such as test.html.

So if you request /test.html, the server appends /test.html to /mnt/skyeye/mlswwwn and opens the file /mnt/skyeye/mlswwn/test.html.

Now, if you request /../../../etc/passwd, the server serves the file /mnt/skyeye/mlswwwn/../../../etc/passwd. Since .. means “go a directory up”, this resolves to /etc/passwd, which contains a list of users on the system.

Retrieving password hashes

We can also try to request the related /etc/shadow file:

$ curl --path-as-is "http://192.168.2.16/../../../../../etc/shadow"

root:r.BF8RVw56BOA:1:0:99999:7:::

ftp:!:0::::::

usb:w.rW11jv2dmM2:13941::::::

This file contains the password hashes. The shadow file is normally only accessible by the root user, which indicates that the web server runs as root.

Missing privilege separation

The root user is the user with the highest privileges on a Linux system. Running the webserver as root introduces a security risk, since any vulnerability in the web server gives total access to the system. It is generally recommended to run the web server as a normal user that only has the necessary privileges.

Cracking password hashes

Now that we have the password hash, we can try to brute-force it: we try many passwords and compare their hash to the root user hash. This can be done automatically with a tool such as hashcat. After a couple of seconds, it outputs that the password is 123456:

$ cudaHashcat-2.01/cudaHashcat64.bin -m 1500 -a 3 "r.BF8RVw56BOA"

cudaHashcat v2.01 starting...

...

r.BF8RVw56BOA:123456

This is an insecure password. However, this may not matter much since we haven’t found any place yet where we could login using this password.

Finding files

We now can retrieve any file if we know the filename, but of course we can’t request a directory listing. So we have to guess some paths. We know that the system is running some Unix variant, possibly Linux, since it has the /etc/passwd file. So we can try some common files to learn more about the system.

/var/log/messagescontains a log line about/mnt/skyeye/wifi/wpa_cli-action.sh./mnt/skyeye/wifi/wpa_cli-action.shcontains a call toudhcpcwith/mnt/skyeye/wifi/default.scriptas parameter./mnt/skyeye/wifi/default.scriptrestarts/mnt/skyeye/bin/ota_upgrade.ota_upgradedownloads the firmware image. The firmware image contains all the files.

Analyzing firmware download

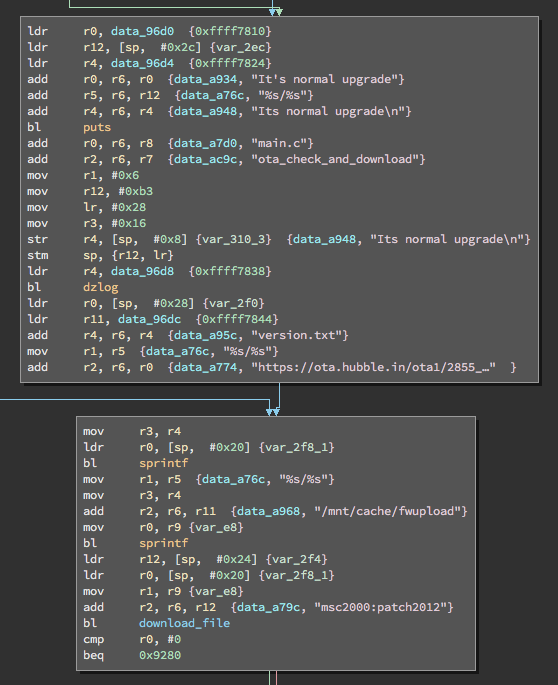

The file ota_upgrade is an executable binary (i.e. an .exe file) that downloads and unpacks the firmware. We can see if we can find out how it does that and then download the whole firmware ourselves, so that we can analyze it.

I load the file in Binary Ninja, a disassembler. I am not very good at ARM assembly. I mainly look at function calls and which strings go into that. For example, bl sprintf calls the function sprintf in the C libary. The three strings above it are probably its arguments. It seems to glue two strings together with a slash between them, which results in the url https://ota.hubble.in/ota1/2855_patch/version.txt. A little further down it uses this version to download the file https://ota.hubble.in/ota1/2855_patch/2855-02.10.08.fw.pkg, which is the firmware image.

Unfortunately, there seems to be nothing on that URL. The firmware image is not available. It could be that I made a mistake when analyzing the code, or that the firmware update process is broken or disabled.

There is something we can try: another code path downloads version_dev.txt, which is supposedly the development version of the firmware. That returns version 03.10.17, and that firmware image exists on https://ota.hubble.in/ota1/2855_patch/2855-03.10.17.fw.pkg.

Now we have the development firmware image, and we want to unpack it and view the files in it. First, we need to decrypt it. ota_upgrade calls aes_decrypt to do this, and we can too. We download aes_decrypt using our path traversal vulnerability. This is a binary compiled for ARM processors, so we can’t directly call it. Instead, we use Qemu.

We copy aes_decrypt, qemu-arm-static, and our firmware image into a directory. Then we run aes_decrypt on our file, in a chroot:

$ sudo chroot . ./qemu-arm-static aes_decrypt 2855-03.10.17.fw.pkg

ERROR opening stdin. Abort!

It fails. Let’s see what went wrong by adding -strace to the command:

open("/proc/self/fd/0",O_RDONLY) = -1 errno=2 (No such file or directory)

We don’t have a proc filesystem in our chroot, so this fails. We can solve this by putting our firmware image file on this location.

mkdir -p proc/self/fd

cp 2855-03.10.17.fw.pkg proc/self/fd/0

We run it again, and now it succeeds. It created a file proc/self/fd/1, which is a tar.gz file with a JFFS2 filesystem image in it, with all the files.

Intercepting HTTPS traffic

So far we have just contacted the camera directly, but we can also try to intercept HTTP traffic to the internet. To do this we set up Burp to act as an invisible proxy and send all HTTP traffic to Burp using a port forward in pf or iptables. Then, when we boot up the camera, we see the traffic it sends to the internet.

This shouldn’t work. We just performed a man-in-the-middle attack on the camera, and that is precisely what HTTPS is supposed to prevent. Hackers intercept SSL traffic all the time, but then they configure the client to explicitly trust the certificate Burp uses. In our case, we can’t tell the camera to trust us. Still, we can view all traffic.

This means that the camera doesn’t actually verify SSL connections. It communicates over HTTPS, but since it doesn’t verify certificates this can be intercepted by anyone with access to the network. The security of HTTPS is effectively disabled.

Furthermore, when you enable motion detection on the camera it sends a camera picture over plaintext HTTP over the internet. This means that camera images can be viewed by anyone with access to the network path. And if we browse to https://ota.hubble.in/, the browser notifies us that the connection is insecure because the certificate has been revoked.

Conclusion

This camera was insecure, particularly because was is missing authentication and had a path traversal vulnerability in the web server. I reported these vulnerabilities to the distributor, who took it seriously and has deployed fixes through firmware updates.