Combining CSRF and timing attacks

In a CSRF attack it is typically not possible for the attacker to retrieve the result of the forged requests. In this post we show that by measuring the time that a forged requests take we can extract some information, for example whether a specific resource exists.

Limits of CSRF

CSRF uses the fact that a user is logged in on one site to do requests on behalf of that user on another site. This way the attacker can trigger actions on the site the user is logged in, even though the attacker has no access to the site.

Normally, this method cannot be used to get information from the other site. It is possible to include another site in an iframe, but it is not possible to read the contents of that iframe with Javascript

<iframe src="http://127.0.0.1/" id="iframe"></iframe>

<script>

$('#iframe').on('load', function () {

console.log($('#iframe').contents()); /* Fails:

Uncaught SecurityError: Failed to read the 'contentDocument' property from 'HTMLIFrameElement': Blocked a frame with origin "http://localhost" from accessing a frame with origin "http://127.0.0.1". Protocols, domains, and ports must match.

*/

});

</script>

However, there is a little bit of data that can be extracted cross site by measuring how long it takes to load the page in the iframe.

Timing iframe loads

When an iframe is finished loading it triggers the load event. This also happens when the iframe contains cross site content, and even when the X-Frame-Options header denies the content from loading in an iframe. By putting an iframe on the page and measuring the time until the load event, we can determine how long it took to load the page.

function measureUrl(url) {

var start;

var iframe = $('<iframe />');

iframe.attr('src', url);

iframe.css('display', 'none');

iframe.on('load', function () {

var time = Date.now() - start;

console.log(url, time);

});

start = Date.now();

$('body').append(iframe);

}

The function above places an iframe on the page and measures the time it takes for the load event to trigger. This can for instance indicate whether a resource exists.

Practical example with JSPWiki

Suppose the victim works for Monsters, Inc. At Monsters they use JSPWiki internally. It is not accessible from the Internet, but the attacker wants to retrieve some information from it. The attacker suspects that Monsters is going to merge with another company. He wants to know whether this is true, and which company Monsters is going to merge with.

The attacker can create a page that measures the time of some URLs on the wiki:

var urls = [

'https://wiki.monsters.inc/Search.jsp?query=%22merger+with+Acme%22',

'https://wiki.monsters.inc/Search.jsp?query=%22merger+with+Blaze%22',

'https://wiki.monsters.inc/Search.jsp?query=%22merger+with+Contoso%22',

'https://wiki.monsters.inc/Search.jsp?query=%22merger+with+Duff%22',

];

for (var i = 0; i < urls.length; i++) {

setTimeout(measureUrl.bind(this, urls[i]), i * 1000);

}

The JSPWiki search page is slower when it has any results, so the attacker can deduce which wiki page exists and thus which company Monsters is going to merge with.

On my test setup with JSPWiki the search page is about 30ms slower when it has any results. This makes it necessary to measure multiple times to get an accurate result, but it is also enough to make this attack work over the Internet.

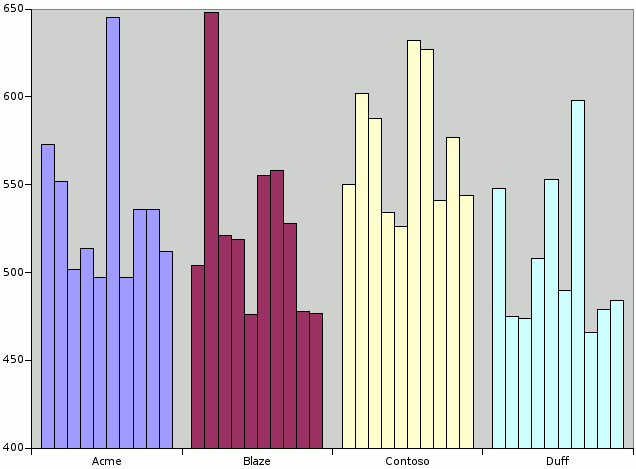

The chart shows times in milliseconds for 10 samples for each suspected company. Contoso has a higher average time to load. It is likely that Monster is going to merge with Contoso.

Since the time difference is so small and depends on the specific JSPWiki configuration, this attack would be hard to reproduce in a real-world scenario. Furthermore, JSPWiki’s security model is to protect the page contents, not the page titles. The developers of JSPWiki decided that they would not consider this timing attack a security vulnerability.

Conclusion

It is possible to detect timing differences using forged requests. There are several requirements for an application to be vulnerable:

- The request needs to be predictable. Just like any other CSRF attacks, this one can be protected against by requiring a secret token when submitting the request.

- The server must allow cross origin requests. If the server checks the referrer header, request forgeries are not going to work.

- The response must have a noticeable timing difference. There has to be at least some milliseconds difference between responses, otherwise the difference is too small to measure using iframes and Javascript.

Update

Hemi Leibowitz and Nathanel Gelernter call this style of attack a cross-site search attack, or XS-search. They use reflected input to inflate the response size, increasing the time difference between positive and negative responses.