Compression side channel attacks

Compression side-channel attacks can be used to read some data by knowing only the size of the compressed data. Recently compression side-channel attacks have been published on compressed HTTPS connections: the CRIME, TIME, BREACH and HEIST vulnerabilities. This post describes how compression side-channel attacks work in general and what these attacks do in particular.

How compression works

Compression algorithms such as gzip use two tricks:

- The most often used letters get the shortest representation.

- Any phrase that is repeated only gets stored once.

We will focus on the second trick: if a certain string of characters is repeated somewhere in the text, it is only stored the first time. The second time it occurs a reference is included to the first occurrence.

Consider what happens when we compress this quote:

Build a man a fire, and he’ll be warm for a day. Set a man on fire, and he’ll be warm for the rest of his life.

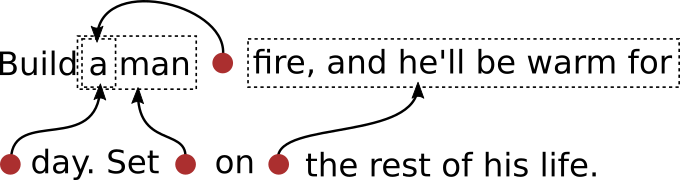

As you can see, there are several parts that occur more than once, particularly the part “fire, and he’ll be warm for”. Gzip stores this by referencing an earlier position when a repeating phrase is encountered.

This image shows the references of the compressed file. The first red dot in the sentence references an earlier use of “ a “, for example. This way, we only have to store 69 characters and 4 references instead of the original 115 characters.

The key point is that when a text occurs multiple times it is very efficiently compressed. If much of the text is the same, the compressed size is smaller. We can use that fact in a compression side channel attack.

How a compression side channel attack works

As we learned previously, compression works efficiently if a phrase occurs multiple times in a text. This means that if a text contains both a secret and a user-controlled part, we can guess the secret by just looking at the length of the compressed result.

For an example, consider a web site that uses compressed and encrypted cookies. Some of the values in the cookie are secret, and some can be set by the user. Because the cookie is encrypted, we cannot read the secret straight away. Assume the plaintext cookie looks like this:

secret=tops3cr3t&favorite_color=red

Users can set their own favorite color. What happens if we set our favorite color equal to the secret?

secret=tops3cr3t&favorite_color=tops3cr3t

Because the phrase tops3cret now occurs twice, this compresses very efficiently. By just looking at the size of the cookie we can see that our favorite color tops3cr3t is present somewhere else in the cookie.

In most cases you can even guess one character at a time. Simply try “a”, “b”, etc. as your favorite color. When the size of the cookie drops by one byte, you know you have guessed the first character right.

This only works if the secret and the data controlled by the attacker are compressed together, and we can read the size after compression.

Demonstration page

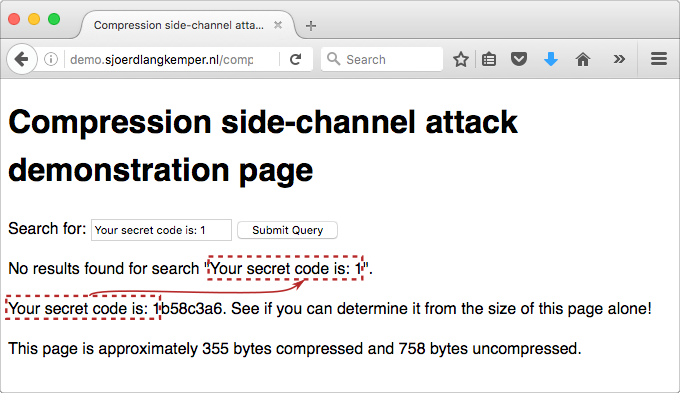

Try your hacking skills on the compression side-channel attack demonstration page. This page satisfies the conditions needed for a side-channel attack:

- It compresses the whole page using gzip HTTP compression.

- It reflects part of the input, which gives an attacker control over the compressed data.

- It has a secret token on the page.

Of course in this demonstration you can simply see the secret, but the point is that you could also determine it by just looking at the page size alone.

Try searching for “Your secret code is: a”, “Your secret code is: b”, etc. Note that the size decreases by one byte if you guessed a character correctly. Because the same text occurs twice, it is more efficiently compressed.

Practical applications on HTTPS: CRIME, BREACH

We learned that an attacker can read some data if:

- he can read the size of the compressed page,

- and he has control over some of the data on that page.

This may be the case for a man-in-the-middle attacker. Suppose this attacker wants to obtain the CSRF token of a web site that is served over HTTPS. We assume the attacker can make requests to the web site, for example by injecting HTML tags or Javascript into other (non-HTTPS) web sites. He cannot read the result because it is encrypted, but he can read the size. If the web page also reflects some of his input, he can attack the web site using a compression side-channel attack.

This is the basis for the CRIME and BREACH vulnerabilities, where CRIME depends on compression on the transport layer and BREACH depends on HTTP compression.

With these vulnerabilities, a man-in-the-middle attacker can obtain a CSRF token by performing many requests and looking at the response size. Just like above, the attacker would do requests like “csrftoken=a”, “csrftoken=b”, etc. In order to work, the requested page need to both reflect this input and contain the CSRF token itself.

Timing attacks: TIME, HEIST

Whereas CRIME and BREACH only work for man-in-the-middle attackers, TIME and HEIST work from the browser for any remote attacker. Instead of reading the size from the network, timing information is used to determine the response size. By carefully timing how long it takes to receive a response, the exact size in bytes can be determined. This can be done with Javascript, so this attack can now be performed from within the browser.

Mitigation

There are several ways to protect against these attacks.

You can disable compression. This obviously makes compression attacks impossible. It also decreases performance, since compressed pages are typically transferred faster. A nice trade off is to only enable compression if the referrer header matches the correct host. This enables compression for requests from the same site, but disables compression for cross-origin requests.

Another possibility is to randomize secrets for each request. If the CSRF token is random each time, the attacker cannot use multiple requests to guess it.

A promising solution is the same-site cookie flag. This makes it possible to mark cookies so they are withheld on cross-origin requests. This means that if an attacker forges requests from his website, these requests do not contain session cookies and are handled as if they come from an anonymous user. This solves many types of CSRF-related attacks, but is unfortunately not yet supported in all browsers.

Conclusion

Compression side-channel attacks are feasible if a secret and some user input are compressed together, and the attacker can read the size of the compressed response.

Where CRIME needed a specific situation of a man-in-the-middle attacker on a compressed connection, the more modern HEIST attack can be executed in the browser. This poses a real threat to applications that support HTTP compression and reflect some user input.

Read more

- Compression and information leakage of plaintext - John Kelsey

- CRIME slides - Rizzo & Duong

- TIME paper - Be’ery & Shulman

- BREACH web site - Prado, Harris & Gluck

- HEIST presentation - Vanhoef & Van Goethem